Rachel Killing a Baby Is Just as Bad as Watching It Drown

A young mother ambling across Wimbledon Common with her dog and her immature son on a perfect July forenoon in 1992. A frenzied attack from an unknown assailant. A media circus. A botched police investigation.

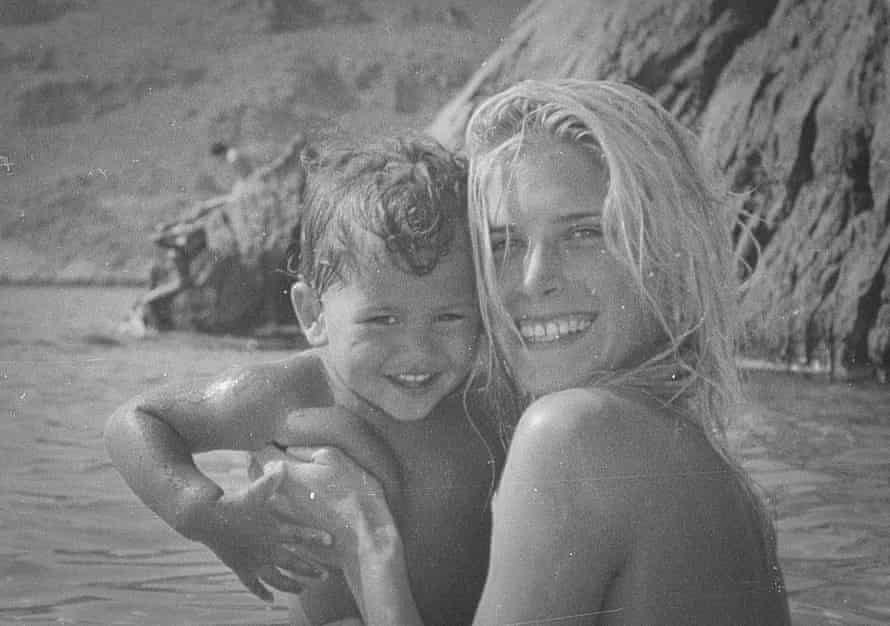

The murder of Rachel Nickell was one of the about high-profile crimes of the last few decades. Her name conjures an instant picture of her blond pilus and laughing face. The names and faces of her young son – who witnessed the set on – and her bereft partner, Alex and André Hanscombe, are probably less familiar, which is just every bit they wanted it. Unable to live in the spotlight, they left the Britain but months afterward to begin once again. Now, 25 years later, side by side in a hotel bar in sunny Barcelona, grinning, relaxed, this tight father and son team seems a kind of phenomenon.

Alex, 27, has written his own business relationship of his mother's murder, its touch on and aftermath. It's as he remembers it – through the eyes of a child. Though he was just three weeks short of his tertiary altogether when it happened, he was able to provide police force with a strikingly accurate account of the attack and the assailant, and it remains crystal clear in his heed.

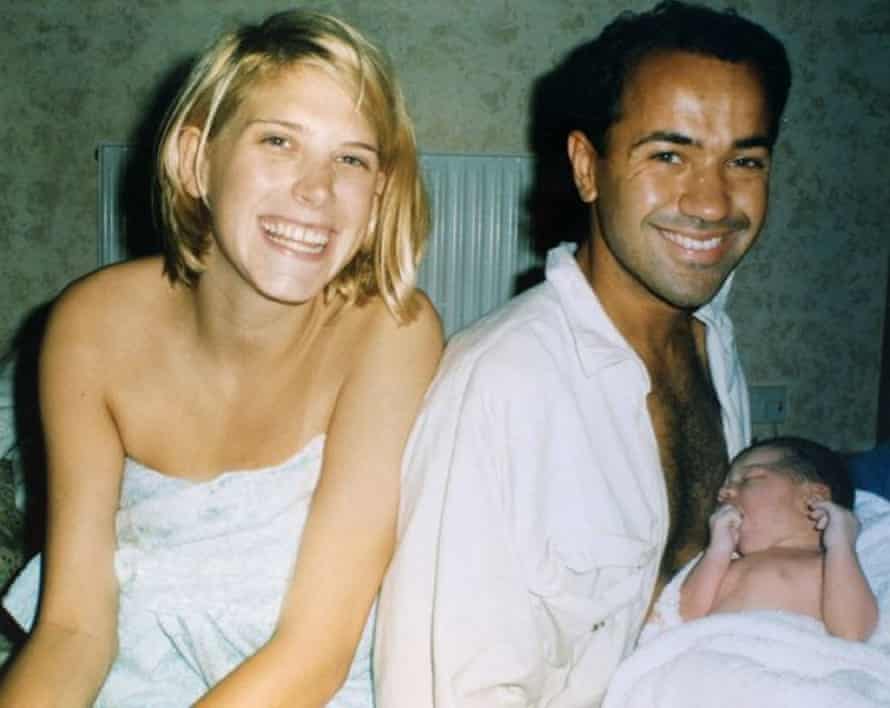

At that time, Rachel Nickell, 23, lived in Balham, s London with André, Alex and their rescue dog, Molly – she called them her "little pack". She had met André at a swimming pool when she was just 19, lifeguarding. A erstwhile grammar-schoolhouse daughter, Rachel was studying English literature at university; André was a semi-professional lawn tennis player. After their first date, Rachel phoned her mum to say she had found the homo of her life. Within months, she was pregnant, had quit her studies and moved into André'due south flat. He'd started work equally a motorbike courier to make ends meet. The plan was to sell up, get out the UK and live somewhere rural – France was superlative of the listing.

"I remember waking upwardly on the morning time it happened, waving cheerio to my father, watching him fire upwards his wheel for work," says Alex. "The journey across town to the common has kind of disappeared, but I think walking along the path in the woodland."

All of a sudden, a man appeared from nowhere. Alex later on described him to police: his loping walk, his strange, blank confront, his black purse, white shirt. He threw Alex to the basis – and past the time he had recovered himself, the man was down at the stream, washing his easily before lurching away. Rachel – who had been stabbed more than 40 times – lay utterly still.

"It'south non like it happens in the movies," says Alex. "Information technology was so quick, and everything was silent. At that place was this strange polarity – even though it was hectic and violent and there was blood, at the aforementioned fourth dimension, in that location was this large feeling of peace and tranquillity. To me, my female parent but looked like she was lying there, fix to wake whatsoever moment, like in the imaginary games nosotros used to play."

Alex asked her repeatedly to get up – only Rachel didn't reply. "That'southward what I recollect most," says Alex, "the particular moment I knew she was gone. That feeling of losing someone y'all beloved, how everything tin can change in a matter of seconds."

It seems extraordinary that Alex never asked for Rachel again, or wanted an explanation for where she was or what had happened. In his picayune world, he'd already formed an understanding of death. The family unit had recently rescued a bird with a cleaved fly, which thrived for a while and so died. They had buried it on Wimbledon Common and Rachel had explained he "didn't need his body whatsoever more than", the part that was "really him" had "gone somewhere else". Alex had also been transfixed past the children's film The Land Before Time only days before the attack, where the mummy dinosaur dies in an earthquake and the infant pleads for her to get up, earlier conveying on without her.

On the common, the alarm was raised, an ambulance called, and Alex sedated. From the moment André collected him from hospital, Alex transferred all his needs, his love and emotion to his begetter. When Alex woke next morning, he asked immediately for "Daddy" – until that day, it had been "Mummy" every time. In the post-obit weeks, Alex wouldn't let André out of his sight.

It'due south impossible to imagine how André functioned, raw with shock, deep in grief, the focus of a media frenzy and sole protector of a traumatised child – who was besides the only witness to the murder, the best possible source for leads.

"It was mind-bending the whole fourth dimension," says André, "and in that location wasn't anybody I could go to for help because information technology was one of those farthermost experiences that very few people had encountered."

Rachel was his reference point. "Nosotros'd had a adequately normal dynamic," he says. "I went to work, Rachel was home with Alex. The two were a unit, a circle, and I was on the outside, controlling the perimeter. I didn't take in all the details of Alex's mean solar day because it wasn't my responsibility. But 'normality' for a three-yr-old ways getting the toast right, the showers at the correct time, the juice in the right cup. For every decision I made, from the nearly unimaginably trivial, I'd inquire myself: 'What would Rachel take wanted?' And because I knew her so well, because nosotros had that connection, that'southward what I leant on."

That – and Alex himself. "The fact that he'd switched all his passion and attention to me was overwhelming but also a massive aid," says André. "It was soothing, a lotion. That dear and amore keeps yous afloat."

From the outside, the decision to leave v months later, just the two of them and Molly the canis familiaris, seems farthermost. Their showtime finish was the south of France, where they rented a remote farm building near Montpellier. Iii years later, they crossed over to Spain, settling in Catalan countryside, where André coached tennis. They told no one about their past.

Starting over was, says André, a nightmare. But the alternative was worse. Normal life in the UK had seemed impossible, unreachable. The press had followed Alex to nursery. The police force had wired their home in example Alex revealed a crucial detail. They had been taken to gruelling sessions with a child psychologist, which felt all wrong.

"All the time, you run into the headlines, you hear the whispers, everyone'south watching Alex, saying he'll never recover," says André. "I just felt it was impossible for a kid to grow up like that. Rachel and I were always going to get out the country – again, it was being true to her values."

Rachel's parents were devastated by their departure, describing it as a second bereavement. However, their relationship with Alex continued, with Alex visiting until the age of viii, when contact ceased. (They accept corresponded more than recently.) According to André, this was never intended – Rachel'southward parents had already lost plenty, he says. "For years," says André, "life was a fog." He battled "waves of grief", and was often captivated by the murder and all he had lost. "There were times when all I thought about was revenge," he says.

The police had quickly identified Colin Stagg as the attacker, a loner who fitted Alex's description. With no evidence, their endeavor to "play a trick on" Stagg into a confession using an undercover female person constabulary officer as bait was thrown out of court. Withal he remained the only doubtable.

Alex never asked nearly the case, or what had happened to the "bad man", but Rachel's presence remained shut. "She was a natural part of the day," says André. "Alex might describe a film and say, 'Mummy would take liked that.' He had the aroma she wore in his drawer with his favourite things and he'd get that out. I could run into him connecting with the memories, getting comfort from that."

By mean solar day, Alex seemed to exist recovering well. "He had a huge corporeality of freedom," says André. "He ran wild with the bikes and the dog, he quickly fabricated friends, he was sociable, no signs of fear." Just nights told another story. "His nightmares had started very shortly after the attack and went on for years. He'd make these terrible, alien sounds of distress, he was catatonic, his eyes were open and I couldn't reach him. The relief, over time, was seeing them dropping in intensity, becoming more than spread out. At that place was comeback. In that location was hope."

Neither had therapy; no one supported them. André thought of turning to a local priest but in the terminate, he realised day by day, just getting by, living life was their recovery. Inevitably, there were tensions.

"All the pressures on my father, having to make so many decisions, being isolated – sooner or later, the tensions were directed at each other," says Alex. "We had a lot of fights and that really reached boiling signal in my teenage years." André agrees: "We were at war. Two males. Large personalities. Me setting boundaries and him trying to break them."

It was only after Alex left home to study music in London that their human relationship recovered. André recalls the turning point. "Teenage kids phone dwelling house for a reason – to ship money," he says. "We had the usual conversation about resources but then Alex didn't end the call, he wasn't running away to do something else. He started request me: 'Then, how are you?' He was sensitive, there was and then much emotional intelligence. I put the telephone down and thought: 'I'yard dealing with a grownup.'"

Rachel's killer – Robert Napper – was not identified until 2004. Past then, he was already living in Broadmoor loftier security psychiatric infirmary after committing more than 100 sexual offences and, in November 1993, brutally murdering some other mother, Samantha Bisset, and her iv-year-old daughter, Jazmine. In December 2008, he pleaded guilty to Rachel'south murder. Alex and André say they feel no anger towards him – nor towards the police for their catastrophic focus on the wrong homo, Colin Stagg.

"I'd been very aroused for a very long fourth dimension," says André. "Just reading the psychiatric report and seeing what Robert Napper had been through, he'd had a violent dwelling-life, he'd been sexually driveling. I'd ever told Alex that nobody'south better than anybody else. You have to try to understand why they do things. Forgiveness is a process and over the years, almost without knowing it, I'd been through mine and Alex had been through his."

André likewise wrote a alphabetic character of apology to Colin Stagg for publicly pointing the finger towards him. "Every bit a parent, you lot take to fix an example," he says. "I can't expect Alex to behave in a certain mode if I wasn't prepared to do information technology myself. I made a mistake – based on data from patently reliable sources. I helped put a spotlight on him, which made his life worse."

A few years subsequently, Alex and André decided to go travelling together. "It was a completely different dynamic by then, both adults, no obligation," says André. "Nosotros airtight everything down, gave away what we couldn't sell, then spent four years on the route – India, Egypt, Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka …"

Alex'south volume began along the way. "When we told people the story, it was amazing how moved people were," says Alex. "People from completely different walks of life who knew nothing about us were inspired. I was the 'tragic tot' but we'd both got through. Everyone has challenges and obstacles and fears. My message is: 'There'south light at the terminate of the tunnel.'"

Though there accept been other relationships, André is single and he and Alex at present live in Barcelona. He sees Rachel in his son every day. "Her sharpness of intelligence, her wicked sense of fun and her movements, too. Rachel was tall and elegant – a dancer. Alex has that same elegance, you run across it in his gestures, his optics, his presence.

"Nobody does everything right – and I don't know how I did anything, looking dorsum on it," André continues. "It's been a marathon. But I can look at Alex now and call back: 'I'k in clear h2o.' Mission accomplished. Alex got me through – and Rachel."

crooksofamidentam.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/may/27/rachel-nickell-son-husband-andre-alex

0 Response to "Rachel Killing a Baby Is Just as Bad as Watching It Drown"

Post a Comment